ESSAYS

Johnathan Goodman on Sarah Hinckley’s paintings

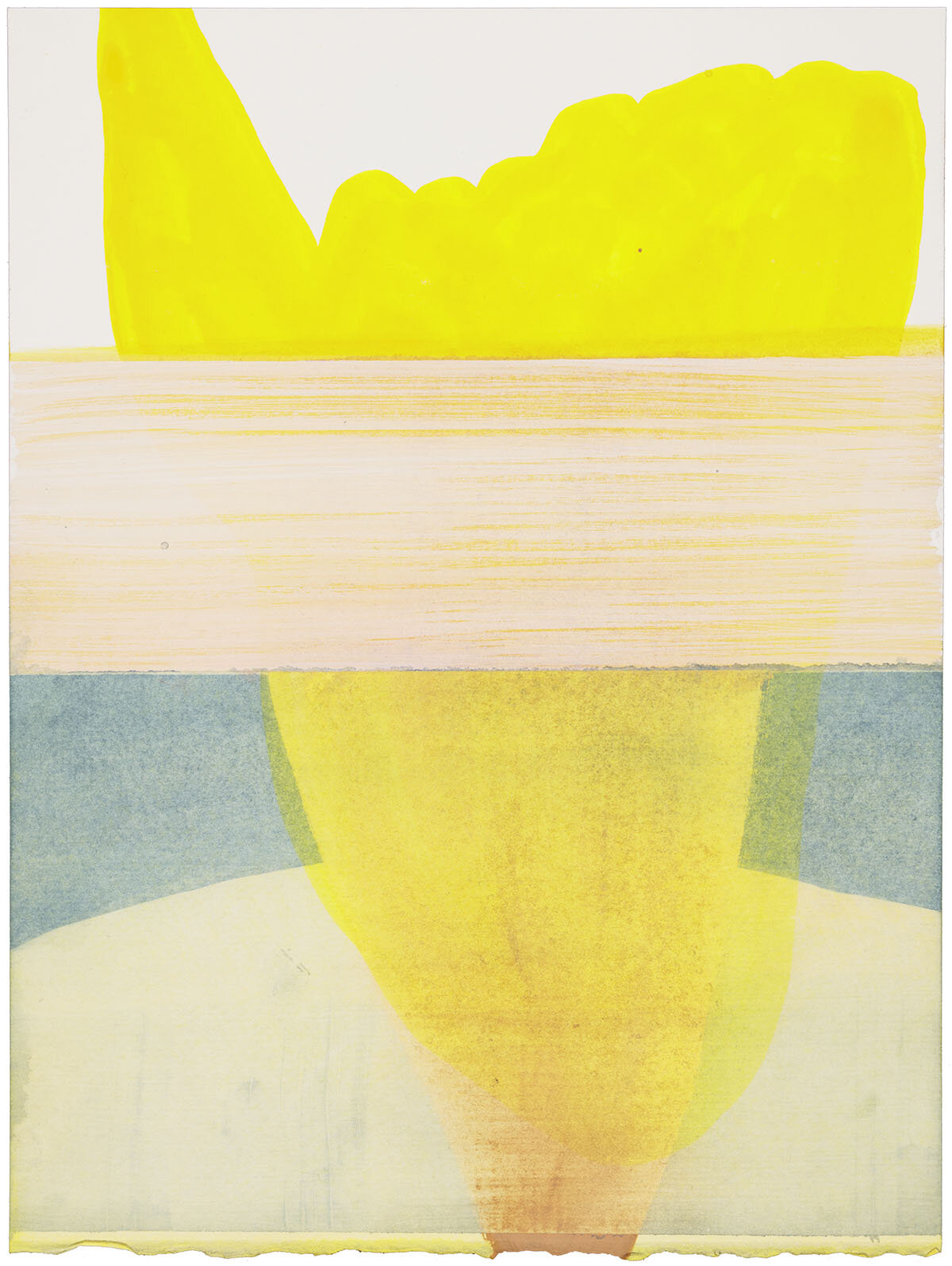

i watch them bloom (10), 12 x 9 inch watercolor, 2020

i watch them bloom (9), 12 x 9 inch watercolor, 2020

Sarah Hinckley grew up in Cape Cod, and her airy, sumptuous artworks reflect the sea and open skies of the geography found there. She also studied and worked in New York with its ongoing tradition of abstraction, which influences her current mature style which follows a path established by Mark Rothko and Agnes Martin, both proponents of a painterly, poetic abstraction. This combination of openness and subtle nonobjective effect recalls both a particular locale or place, and a painting tradition that contributes to a present-day lyricism that feels familiar, made so by our awareness of an especially American point of view. However, Hinckley’s style is very much her own, driven as it is by an abiding concentration directed toward the minimal and reductive effects of contemporary abstraction. Her work cannot be said to exist as a series, yet similarities between paintings or works on paper indicate that her efforts are part of an encompassing whole. The large and open central spaces occur along a continuum that unifies our visual experience of her approach and thinking process.

Perhaps the most engaging aspect of Hinckley’s painting is the combination of her attraction for minimal or simplified imagery, combined with her penchant for creating a visually gratifying work of art. She does in fact do this, realizing the shapes in her art, which are usually organic in nature, link her paintings with an esthetic of elegant simplicity. Yet we cannot see the art as merely simple or reductive; instead, its eloquence and lyricism originate in the Hinckley’s willingness to present a unified field of painting in which the poetry of her observations, no matter whether they occur on the edge or in the center of her compositions, communicates the openness of an unobstructed view. The results are not so much an alternative as a variant on mainstream painting. Thus, her lyricism and her feeling for structure are equivalent. This means that the emotional content cannot be separated from its formal expressiveness, which can only happen when an artist’s work is both strong and compelling.

The paintings tend to be defined by their peripheral effects, while the works on paper are less sparsely populated. In both cases, the organic is emphasized--this is not hard-edged geometric work, although Hinckley’s soft-edge organicism is resolutely nonobjective. Today, abstraction in art remains viable, in large part because painters like Hinckley keep it alive in displays of imagery that both challenge our sensibility and at the same time address a need for a beauty that cannot be easily dismissed. Indeed, beauty is key to our perception of Hinckley’s art, which refuses any excessively easy avenue of attractiveness even as it makes its claims based upon poetics that can be linked both to the pastoral and the urban. Thus, the rounded shapes and more linear forms that coexist in her watercolors are interesting because they tied together by color. In fact, color should not be seen as a secondary, but rather a primary interest in her work, which retains a persistent reading of nature even as its repertoire of styles link it to historical and artistic advances in New York abstraction. This means that our experience of Hinckley’s accomplished sensibility is a complex one, aided by her persistent regard for shape and color’s ability to build nearly celestial (but also earthy) structures on their own.

–Jonathan Goodman, Summer 2020

More essays

Follow Sarah on Instagram